Clik here to view.

Alleged druglord Vicky Goswami and Bollywood star Mamta Kulkarni are believed to be in a relationship since ’90s, though they deny it

Alleged druglord Vicky Goswami and Bollywood star Mamta Kulkarni are believed to be in a relationship since ’90s, though they deny it

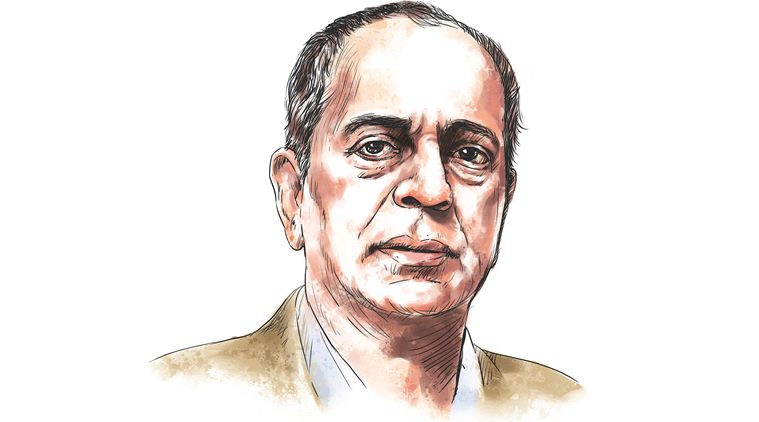

A bootlegger from Ahmedabad lands in Mumbai, meets Bollywood star Mamta Kulkarni, crosses countries and ends up as an alleged druglord. MOHAMED THAVER tracks the story of Vicky Goswami, who now has the US Drug Enforcement Agency and the Thane police hot on his heels.

BACK IN the ’90s, large black suitcases started appearing as luggage, mostly on flights headed from Mumbai international airport to Cape Town in South Africa. There was something unusual about these bags, though. No passenger seemed to be accompanying them. A Mumbai Police team of ‘encounter specialists’ such as Pradeep Sharma and Daya Nayak would later find that at least five similar black bags were put on planes at the international airport every day by airport loaders.

Photocopies of the airport luggage tags of these bags would be faxed to Cape Town, from where another person would collect these bags. “Each bag had nearly a thousand tablets of Mandrax. We laid a trap several times but no one ever accompanied these bags,” says an officer who was then part of the Anti-Narcotics Cell. Police would later identify the man behind the cartel supplying Mandrax tablets as Vijaygiri ‘Vicky’ Goswami.

For long after that, even as the officers moved on to other units, Goswami went about his business. His cover was blown in 2014 when he was detained in Kenya with former Bollywood actor Mamta Kulkarni. While Kulkarni was eventually allowed to go, her resurfacing from oblivion along with an alleged druglord created a buzz around the identity of the person she was found with. “There are hundreds of people like Vicky operating such cartels about whom no one knows. The fact that his arrest got so much attention because of Mamta Kulkarni destroyed the veil of anonymity he had enjoyed earlier,” says an officer with the Anti-Narcotics Cell who had tracked Goswami.

The Drug Bust

On April 18, the Thane Police arrested a Nigerian national who was allegedly selling ephedrine on the streets of Kalyan. This led to a series of arrests of drug peddlers that eventually led the Thane police to the office of Avon Lifesciences Ltd, located in Solapur, Maharashtra, from where they recovered 18.5 tonnes of ephedrine worth Rs 2,000 crore. On April 27, police arrested Manoj Jain, one of the directors of Avon Lifesciences. Jain’s interrogation revealed that he had gone to Africa several times and met Vicky Goswami. Police believe Goswami was to receive the ephedrine and use it to cook meth at a factory in Mombasa and supply it to several countries. The police are still on the lookout for at least two accused — Kishore Rathod, son of a former Gujarat legislator, and Jay Mukhi, a friend of Rathod’s.

What’s Ephedrine?

Ephedrine is popularly used overseas to treat asthma and bronchitis. While controlled dosage eases breathing and is also an ingredient in making cough syrups, its abuse, popularly in the powder form, is known to cause euphoria, hypertension and nausea. It is synthesised to produce the popular narcotic methamphetamine. There are strict rules regulating the production and transportation of ephedrine — a company producing ephedrine needs permission from the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB).

The 55-year-old is back in the spotlight with Thane Police Commissioner Param Bir Singh naming him on April 27 as the person who had been coordinating with seven people arrested over an ephedrine drug bust, involving the seizure of over 18 tonnes of the drug from the Solapur unit of Avon Lifesciences Limited.

“Vicky has a large network of supply chain to various countries. He was to use this ephedrine to cook meth (methamphetamine), also known as crystal, and supply it to various countries including the US,” says commissioner Param Bir Singh.

The Sunday Express tried repeatedly to get in touch with both Goswami and Kulkarni, but got no response.

************

The story of Goswami’s journey, from a bootlegger in Ahmedabad to an alleged international druglord who owns a private jet and a chain of hotels, involves several godfathers and, like many such Mumbai stories, a dash of Bollywood.

Gujarat Anti Terrorism Squad (ATS) Superintendent Himanshu Shukla says, “Goswami started supplying drugs in Ahmedabad till he eventually moved to Africa, from where he is now operating the drug empire.”

Goswami was one of 15 siblings born to Anandgiri Goswami, who retired as deputy superintendent of Gujarat Police. The family had moved from their ancestral village in north Gujarat’s Sabarkantha district to Krishna Kunj society at Paldi in Ahmedabad.

There are unconfirmed reports of Anandgiri having been suspended after he was caught bootlegging in the dry state, but local police confirm Goswami sold bootlegged liquor and was notorious for getting into fights in the area. “After one such fight, an FIR was registered against him at the Ellis Bridge police station in Ahmedabad. I believe that was the first FIR to be registered against him,” says an officer with the Gujarat Anti Terrorism Squad (ATS).

Still a small timer, Goswami hit the big league after meeting Bipin Panchal, also a resident of Paldi. “We believe Panchal introduced Goswami to methaqualone, better known as Mandrax. You could say Panchal was his guru,” says the Gujarat officer.

Through contacts in Valsad and Gujarat, Goswami allegedly started supplying Mandrax in Ahmedabad. In the early ’80s, the first Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) case was registered against him in India, again at the Ellis Bridge police station.

In 1993, Panchal himself was arrested by the Ahmedabad Directorate of Revenue Intelligence with a consignment of Mandrax. Goswami would later leave Ahmedabad for Mumbai. Apart from the fact that the city had a strong party circuit always on the lookout for new drugs, Mumbai had another draw for Goswami. The Ahmedabad lad had been a huge Bollywood fan since childhood, and those who know the family say he would often be punished by his father to keep him away from movies.

In Mumbai, the Mandrax he allegedly supplied is believed to have endeared him to the city’s party circuit and, by extension, got him a foot in the door in Bollywood. Police say this also led to his initial forays into underworld and that he developed contacts with Dawood Ibrahim and Chhota Rajan.

Many of the reigning stars of the day were said to be on his speed dial. A party that he held in 1997 in Dubai for the launch of a chain of hotels — days before his arrest that led to a 25-year sentence — is still remembered by old-timers for drawing “anybody who was somebody in Bollywood”. The stars were reported to have returned to India with lavish ‘return gifts’ like mobile phones, then rare, and cars. There were rumours of several stars approaching Vicky for expensive gifts.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

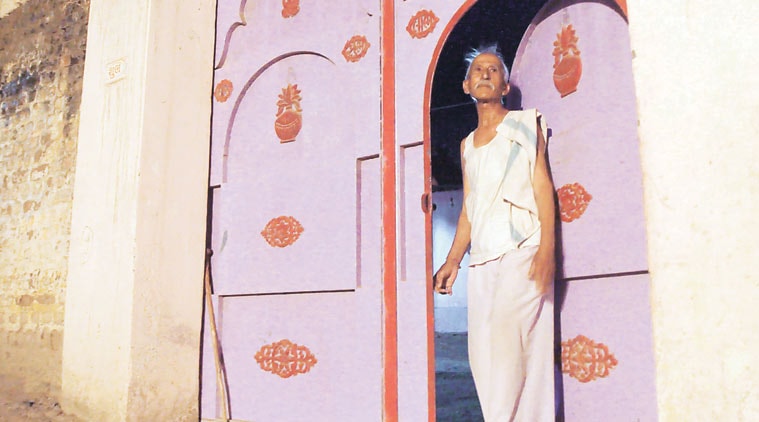

Vicky Goswami’s family home at Paldi in Ahmedabad. Javed Raja

Vicky Goswami’s family home at Paldi in Ahmedabad. Javed Raja

It was through this Bollywood connection that he would meet Mamta Kulkarni, an actress who had films such as Karan Arjun and Baazi to her name.

While her career in Bollywood fizzled out, her name began to be linked to the underworld after rumours that a director had to reinstate her in a movie after receiving threat calls from the underworld.

Goswami and Kulkarni were said to be in a relationship by the late ’90s. While there were reports of them having got married, both have always denied it. In media interviews, Goswami has also rubbished stories of Kulkarni attending meetings in several countries on his behalf to broker drug deals as he could not travel abroad after his passport was impounded following his arrest.

In an interview to Aaj Tak on April 28, Kulkarni dismissed Goswami’s drug links and said his arrest in Dubai was over a family dispute. Kulkarni also said she and Goswami were “trying to establish” their business of imported food commodities.

At Goswami’s family home in Paldi, his brother Dinesh Goswami rubbishes the Kulkarni connection. “Vicky was a bright student who became a pilot in the mid-80s. He got married and has three children who are settled abroad. Mamta is a well-wisher who has turned into a sadhvi,” he says.

************

Parallel to this starry story ran the tale of drugs, and a man shifting countries and continents to escape the law. “The story of the rise of Goswami will not be complete without the story of the rise of Mandrax as the chief party drug of the ’90s,” says an officer of the Ahmedabad police. “Whatever he managed to achieve, be it quick money in a matter of years or his connections in high places, was thanks to peddling the right ware at the right time.”

Adding that most party drugs have a life cycle, the officer says, “In the party circuit, there is this fascination for newer drugs with fancy names. Currently, synthetic drugs like meth are big on the party scene. In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, Mandrax was all the rage.”

That was where Africa came in. An officer of the Mumbai Anti-Narcotics Cell says if India was believed to be the largest producer of Mandrax, African countries were believed to be its largest consumers. Goswami reportedly recognised this early.

“Mandrax is a depressant that causes a drop in blood pressure, leading to a state of deep relaxation. While it was banned in India in 1971, it was a favourite among miners in Africa who would mix it with alcohol at the end of the day for relaxation. From miners, it became popular with schools and colleges there. This was the reason why Vicky shifted to Zambia in Africa from Mumbai, as he saw a huge market there. He set up a factory in Zambia where Mandrax could be produced,” the officer says.

According to a report in the Mail & Guardian, a South Africa based weekly newspaper, Goswami met Irvin Khoza, nicknamed the ‘Iron Duke’, chairman of the Orlando Pirates football club and chairman of the 2010 FIFA World Cup Organising Committee in South Africa. Such powerful friends helped Goswami’s prominence as well as wealth grow in Zambia. However, it also brought him to the notice of authorities, and in 1993, Goswami left Zambia for South Africa.

Once in South Africa, he again established his network and was reported to have built a huge empire, with luxury cars and a private jet. The Mail & Guardian report also says he had to leave the country after coming on the radar of law-enforcement agencies, especially after the death of an alleged drug dealer and socialite, Roberto ‘Rocks’ Dlamini, said to be one of the biggest unsolved crimes in South Africa till date.

************

In late 1996, he moved to Dubai, which had by then become the new address of the Mumbai underworld. In 1997, he was arrested and sentenced to 25 years on charges of drug trafficking. There are several theories behind what led to the arrest of Goswami, who had earlier managed to escape officials of three countries.

An officer says that initially, Goswami was close to underworld gangster Dawood, who, along with Chhota Rajan, controlled the Mumbai underworld. When the 1993 Mumbai serial blasts forced everyone to take sides, Goswami allegedly picked Rajan. “It was this proximity to Rajan that led a D-Company operative to tip off the police that led to Goswami’s arrest,” the officer claims.

This is also believed to have been the reason behind the attack on his house in Ahmedabad. Four people had come in an autorickshaw and fired a round at their house at Paldi in 1993, the officer says.

Goswami’s stint in the Dubai prison would lead to two aspects of his life that he has always denied: his conversion to Islam and his alleged marriage to Kulkarni. In an interview he gave to a TV channel, he said that there were two instances, in 2006 and 2008, when convicts on death sentence in the Dubai prison where he was lodged were granted pardon while he was denied the same.

A source says, “Goswami realised he stood a better chance at clemency if he converted to Islam, and hence converted. He was eventually granted pardon and released in November 2012. His sentence was commuted by 10 years.” Goswami has denied this in media interviews.

Goswami reportedly changed his name to Yusuf Ahmed and Kulkarni to Ayesha Begum, and both got married while he was behind bars as per Islamic rites. Goswami has denied this too, so has Kulkarni. Even after the recent controversy, Goswami has said Kulkarni is just a well-wisher and that he had never married her. Reports of the duo staying together in Kenya continue to surface.

After being released from Dubai, an officer says, Goswami first came to India and then moved to Kenya, where he came in touch with the drug cartel run by the Aksaha brothers, sons of slain drug baron Ibrahim Akasha. In October 2014, Goswami was arrested along with the Akasha brothers, Ibrahim and Bakhtash, by the local anti-narcotics unit in Kenya with assistance from the US Drug Enforcement Authority (DEA). They were charged with conspiracy to traffic narcotic drugs to the US and in Kenya.

The Kenyan authorities also agreed to the US request for extradition of the accused so that they could be tried in a New York court. A Mombassa court eventually released Goswami on bail on the condition that he could not leave the city, even as the hearing for his extradition to the US is in progress.

An officer says that while in the past, Goswami has managed to evade law-enforcement agencies of several countries, it will be a real test for him to keep the DEA at bay.

In his interviews, Goswami has denied any involvement in drug cartels and has claimed to be “doing hundreds of things like coal mining and businesses related to kachcha sona (raw gold)”. He claims it was in connection with the raw gold business that Manoj Jain, one of those arrested by the Thane police, met him in Africa.

“My downfall has been brought about by three people who have been plotting against me all along,” he said in an interview without naming the “the three people”. He added, “Don’t be surprised if they abduct me one of these days and take me to the USA.”

Back at Goswami’s home in Paldi, his brother Dinesh refuses to believe the police’s theory. He says, “Accusing Vicky of every other drug case is like booking Dawood Ibrahim for every murder case. I would never advise Vicky to come back to India. He will rot in jail all his life if he did.”

With inputs from Satish Jha

WATCH INDIAN EXPRESS VIDEOS HERE

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=videoseries&w=640&h=390]Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.