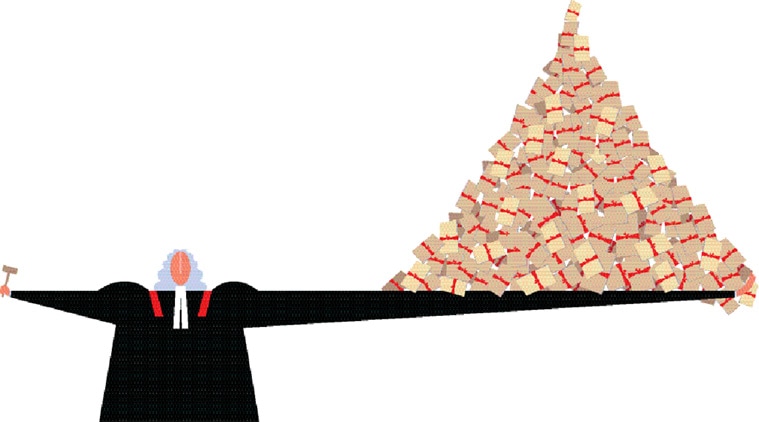

Illustration: C R Sasikumar

Illustration: C R Sasikumar

Last Sunday, addressing the conference of Chief Justices and Chief Ministers, Chief Justice of India (CJI) Tirath Singh Thakur became emotional as he spoke about the shortage of judges in the country, telling the audience, which included Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Union Law Minister D V Sadananda Gowda, that the judiciary shouldn’t alone have to bear the cross for the huge pendency of cases in the country. Referring to the shortage of judges — both in lower and higher judiciary — in the country, the CJI lamented the “inaction” on the government’s part in strengthening judicial infrastructure and increasing the judge-population ratio to deal with the mounting number of cases. While the CJI did manage to put the government on the backfoot, answers to the real issues remained elusive.

First, the facts. India has a total of 21,598 judges (sanctioned strength till December 31, 2015). This figure includes 20,502 judges in lower courts, 1,065 high court judges and 31 Supreme Court judges. However, on the day CJI Thakur made his impassioned speech (April 24), there were six vacancies in the Supreme Court, 432 in the various high courts and a whopping 4,432 (as of December 31, 2015) in the subordinate judiciary.

But, more importantly, if all the 20,502 posts of judges in the subordinate judiciary are somehow filled, there wouldn’t be enough courtrooms to accommodate all of them since there are currently only 16,513 courtrooms —a shortfall of 3,989 — across the country. Judicial infrastructure, it is clear, hasn’t kept pace with the rate of litigation.

In 1987, the Law Commission of India pointed out that the judge-population ratio in India was only 10.5 judges per million population (it is now 12 judges per million) while the ratio was 41.6 in Australia, 50.9 in England, 75.2 in Canada and 107 in the United States. The Commission recommended that India required 107 judges per million population. It also suggested that to begin with, the judge strength could be raised five-fold (to 50 judges per million population) in a period of five years. Almost 30 years later, even that five-fold-increase target looks distant.

The gravity of the situation is all the more pronounced when you consider the fact that there are 38.76 lakh cases pending as on December 31, 2015, in all high courts, of which 7.45 lakh — almost 20 per cent — have been pending for over 10 years.

The situation in subordinate courts is not any better. Of the 2.18 crore cases pending in lowers courts in the country, 1.46 lakh are criminal cases and over 72 lakh are civil cases.

Interestingly, while the Supreme Court saw a rise in the number of cases disposed of over three years — from 40,189 in 2013 to 47,424 in 2015 — the figures for disposal by high courts actually went down from 17.72 lakh to 16.05 lakh in that period.

Subordinate courts too have shown a fall in the disposal rate, with 1.87 crore cases being disposed of in 2013 and 1.78 crore being disposed of in 2015.

The Sunday Express speaks to serving and retired judges, legal experts, including eminent lawyers and policy planners, to find some answers to the vexed issues of pendency and shortage of judges and whether both the judiciary and the government have a plan to deal with these.

Do we need more judges?

“Of course. There is a burning need to increase the number of judges at all levels, including the Supreme Court and the subordinate courts,” says E M Sudarsana Natchiappan, MP and Chairman of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Law and Justice. “But, let’s first start with filling the existing vacancies. In most states, the high courts have taken upon themselves the job of selecting subordinate judges. But the results so far are not very heartening. There are either not enough good applicants… or the judges don’t have adequate time to do this job. Also, there is need for more transparency in appointment of high court judges. Everything should be in the public domain. Put up the names of the candidates on the website at every stage —from the preliminary level to the final stage of President’s approval, with recommendations at various stages. Secondly, civil court fees structure must be suitably modified and it must be made mandatory for state governments to spend the entire fees so collected on building judicial infrastructure,” he adds.

Frivolous litigation as PILs?

Adding to the long list of pending cases are cases such as these: Taking suo motu cognisance, a judicial magistrate in a district court in Mahoba, Uttar Pradesh, in October 2015 registered a case accusing Finance Minister Arun Jaitley of sedition for allegedly criticising the Supreme Court on the issue of appointment of judges. The summons issued to Jaitley were later quashed by the Allahabad High Court. In August 2014, a court in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, directed the police to register a case against Bollywood actor Aamir Khan, filmmakers Raju Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra and others for publication of a poster of their movie PK.

Attorney General of India Mukul Rohtagi says, “I think there is needless interference and no self-restraint by the judges. Too much time is being wasted on cases that are plain frivolous. Frivolous cases that consume too much court time should be dealt with a heavy hand and exemplary costs should be imposed on such litigation. The same must be done for cases where corporates file frivolous cases against their business rivals. The judiciary will have to devise a way to deal with this. Unless this is done, even a ten-fold increase in the strength of judges won’t serve any purpose.”

Former Supreme Court Judge H S Bedi agrees. “Frivolous litigation needs to be tightly regulated. I also agree that in some cases, judges overstep the boundary. They must remember that courts can’t be a substitute for the government.” He also added that while speedy disposal of cases should be a priority, cases must not be dismissed only because it amounts to addition in the number of disposed cases. “Cases must be decided on merit, not because speedy disposal needs to be done.”

Long route to filling vacancies

“It is not possible to fill all vacancies in one go. How can the Chief Justice and collegium of, let’s say, the Allahabad High Court, recommend names for all the 75-odd vacancies that exist right now? For this, they will have to really lower the standard and opt for sixth- or even seventh-tier lawyers. Also, how can the government expect Chief Justices (of high courts) to recommend names when earlier names recommended by them are still under process? But I strongly feel that the existing system of bringing 30 per cent (HC) judges from the subordinate judiciary is flawed since the person who comes at the fag end of his or her career becomes a high court judge only due to seniority. Such a person will only spend their time waiting for eventual retirement. I think either this quota needs to be revised or such elevations must only be on the basis of performance as a judge,” notes Justice Bedi.

Paucity of good candidates?

“Over the years, I have seen a general reluctance among good lawyers to accept judgeship. But I refuse to accept that money is the only criteria behind this. Anybody who accepts it has to do it for the honour, prestige and dignity attached to it. It may be the case that now many good lawyers don’t feel there is enough dignity in being a judge. But this must change,” says former Union law minister and senior lawyer Ashwani Kumar.

Government as biggest litigant

P K Malhotra, who retired as Union law secretary last week, says, “That the government is the biggest litigant is a fact and we are aware of that. But very few people realise that in most cases the government is either the respondent or a proforma party (where the main case is against somebody else). The National Litigation Policy that the government is finalising will deal with this issue, especially the needless and vexatious litigation by government departments. The Legal Information Management-Based System (LIMBS), which we have launched, makes it mandatory for all government ministries to upload all data about pending cases involving them so that we can monitor them.”

Is there a way ahead ?

As a former Supreme Court judge who was a member of the collegium says, there is no “quick-fix solution” to the issue of shortage of judges and pendency.

“It is only in the last 15 years or so that we have started talking about the judicial system and the issues connected to it. Look at the money that the governments were earlier allocating to the judicial sector for creation of infrastructure and hiring more judges. It was dismal, and I am being charitable. However, now both the Supreme Court and Central and state governments are aware of the situation and are working together to find solutions. Funds, while still not adequate, are more freely available and are being spent. In most states, there is a visible change in the infrastructure,” says the judge, who didn’t wish to be quoted.

As per government figures, from Rs 1,245 crore spent on creating judicial infrastructure under the centrally sponsored schemes between 1993 and 2011, the amount went up to Rs 3,695 crore from 2012 to 2016.

Interview with K G Balakrishnan

‘Don’t think retired judges will work as additional judges. Why not appoint regular judges?’

As Chief Justice of India, K G Balakrishnan tried to bring in lawyers to become additional sessions judges for five-year terms and appoint eminent lawyers as ad hoc judges. In an interview with Maneesh Chhibber, the former CJI and ex-NHRC chief says he didn’t see “much enthusiasm” for the scheme.

You tried to get lawyers to work as additional sessions judges. What was the response?

Initially, we tried to appoint lawyers for this post for a fixed period. Some of them were later absorbed in the service. But later, some state governments were not very keen to provide funds to pay their salaries, etc.

You also tried to get regular subordinate court judges to hold sittings beyond normal working hours. Did that work?

We asked judges to sit for two hours (6 pm to 8 pm) after finishing their regular court work. For this, they as well as their court staff were given extra money. In some areas like Bengaluru and Ahmedabad, this worked very well. However, later, many state governments didn’t provide funds for this. So, it fell through. Such a system works wonders in a place where a magistrate has a large number of cases. But for this, the magistrate, his staff, his peon, everyone needs incentives.

There is a suggestion that retired judges could be asked to work as ad hoc or additional judges in the Supreme Court or high courts. Will that help tackle the issue of pendency?

I don’t think many retired judges will be willing to work as additional judges after they have demitted office. Some of them may be holding post-retirement jobs, some may be doing arbitration. Why not appoint more regular judges?

Whose responsibility is it to ensure that all vacancies are filled — the government’s or the collegium’s?

We can’t pin responsibility on any one person or agency. There should be timely recommendations by the collegium, the government must clear the cases quickly and warrants should be issued. As for subordinate judiciary, it is the duty of the chief justice of the respective high court to take the initiative to see that selections are made on time. There is a system already in place, that every year, vacancies that are likely to arise should be calculated and the process for filling those vacancies should begin. Unfortunately, not all high courts follow this.

Does the judiciary have too many vacations?

It was earlier eight weeks and we cut it by one week. Then we tried to cut one more week for the Supreme Court, but there was no unanimity among the judges. Some judges raised objections and said, ‘do it after our retirement’. So I dropped the proposal. But a majority of judges were willing to reduce it to six weeks. It’s not just the judiciary; in this country, we have too many holidays.

WATCH INDIAN EXPRESS VIDEOS HERE

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=videoseries&w=640&h=390]